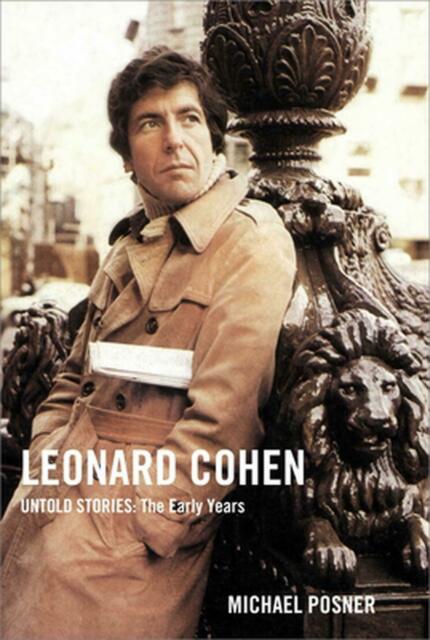

Leonard Cohen – Untold Stories: The Early Years

By Michael Posner

Simon & Schuster

482 pages

Reviewed by Michael Regenstreif

By the time I was a teenager in Montreal in the late-1960s, Leonard Cohen – who was 20 years older than me – was already a legendary, if not mythological figure. His first LP, “Songs of Leonard Cohen,” was released right about the time I was developing a serious interest in both folk music and the contemporary singer-songwriters whose work was somewhat rooted in the folk tradition. So, I began a lifelong relationship with Cohen’s music that has only grown stronger and stronger over more than half a century. And, as a high school and college student, I also read much of his earlier work: multiple volumes of poetry and two novels.

I’ve also had several brief encounters and conversations with Cohen over the years in Montreal and always found him to be exceptionally gracious.

While I’ve read previous biographies of Leonard Cohen, I was anxious to read Michael Posner’s Leonard Cohen – Untold Stories: The Early Years as it’s essentially an edited oral history told through the memories of several hundred people who knew Cohen when he was growing up in Montreal, while he was a student and summer camp counsellor, as a young poet and novelist, and in the first couple of years of his emergence as a major singer-songwriter. The book’s chronology ends in 1970 and two forthcoming volumes of Untold Stories will cover subsequent years. Adding to my interest was that among Posner’s sources are more than two dozen people I know or have known at some point over the years – some of whom (including my cousin, Marilyn Regenstreif Schiff) are people I never knew had a connection with Cohen, while some (like singer Judy Collins) tell stories that I’ve heard directly from them before.

Of particular interest to Ottawa readers will be several pages of stories about the summer of 1956 which Cohen spent as a counsellor at Camp B’nai Brith of Ottawa, as remembered by fellow counsellors such as Evelyn Greenberg and campers like Stephen Victor.

The portrait that emerges over almost 500 pages is of a complex and creative individual shaped by family and circumstance and driven by both spirituality – and a need to find it (the time period of this volume includes Cohen’s brief dalliance with Scientology) – and demons (he is self-medicated with copious amounts of drugs). His transformation from poet and novelist to singer and songwriter is fascinating.

Cohen seems both intensely loyal on some levels and unable to commit on others – particularly in his many relationships with many women, most notably Marianne Ihlen, with whom he had an ongoing, but-mostly-off, relationship through most of the 1960s.

While the stories of Cohen’s many dalliances with women in this book took place in the 1950s and ‘60s, a time of growing sexual freedom and revolution, Cohen sometimes (too often) comes across as predatory in the way he treated women – particularly younger, less experienced women who may have been in awe of him. Reading about some of these encounters is particularly disturbing after all of the #metoo revelations of the past few years.

It’s also interesting to note that some of Posner’s sources had contradictory recollections of the same events and he leaves it to the reader to decide which version is more credible. Of course, given that the events under discussion took place 50, 60, 70, or more years ago, the memories many of the sources will be embellished or diminished by time or, in some cases, wishful thinking.

While the voices of several people who knew Leonard Cohen best in those years – such as his sister Esther, who died in 2014, or his close lifelong friend, the sculptor Morton Rosengarten – are regrettably absent from the book, it is fascinating (and, occasionally, frustrating) to read the “untold stories” of witnesses who were there for the first half of Cohen’s life. I’m looking forward to Michael Posner’s second and third volumes.